Table of Contents

The new shape of big giving

In Africa, generosity has never been in short supply. Tycoons such as Mike Adenuga and Femi Otedola regularly step in with large donations for hospitals, universities or disaster relief, and those interventions often make the headlines. But behind the news cycle, a quieter transformation is underway. A growing number of the continent’s wealthiest business leaders are building structured philanthropic foundations—fully staffed, governed entities that look less like sporadic charity and more like enduring institutions.

The difference is not cosmetic. A staffed foundation can plan a five-year maternal health program, build the data systems to track outcomes, and still pivot if a cholera outbreak strikes. These organizations are designed to outlast a single crisis or a single donor’s lifetime, embedding private wealth into public outcomes. Unlike the ad hoc check-writing of the past, they are laying down scaffolding for sustained giving: boards, audits, strategies, dashboards, memorandums of understanding.

Another feature is their emphasis on partnerships rather than solo acts. The strongest projects are integrated into public systems—schools, hospitals, water agencies—rather than working around them. That model is slower and demands more trust, but it endures. Whether it’s a neonatal ward, an artisan workshop or a rural borehole, the common thread is mobility: the goal is to move people from vulnerability to opportunity.

There are open questions. Who evaluates whether a flagship program is actually working? How are these foundations governed? And what happens when corporate interests conflict with public priorities? Some of the continent’s most visible foundations are beginning to publish strategies, commission independent reviews and disclose multi-year commitments, signaling a move toward accountability.

Still, a pattern is unmistakable. As Africa urbanizes and its young population surges into the workforce, billionaire-backed foundations are choosing long-horizon problems and committing resources to solve them. The money is private, but the intended outcomes are public goods: scholarships that turn into degrees, clinics that lower maternal mortality, research that nudges governments toward better policy.

For a continent long accustomed to measuring wealth in head offices and factories, this is a quieter kind of asset building. And if the next decade is defined by human capital and resilient public services, these foundations will be among the architects.

Today, Billionaires.Africa casts the spotlight on structured foundations owned by African billionaires with clear mandates, governance, staff and multi-year programs. These are the vehicles that can outlast a founder’s news cycle and, in many cases, their lifetime.

What follows is not a ranking of who gives the most but a field guide to the better-known billionaire-backed foundations that operate with the discipline of institutions—setting strategies, measuring outcomes and partnering with governments and multilaterals. In other words: not just gifts, but infrastructure for giving.

Aliko Dangote — Dangote Foundation (Nigeria)

Focus: public health, nutrition, education, economic inclusion

Established long before modern “ESG” vocabulary took hold, the Dangote Foundation has become a cornerstone of large-scale health and nutrition work in West Africa. Its playbook is straightforward: fund high-impact public health campaigns (polio eradication, maternal and child health, nutrition), complement that with education support and small-enterprise grants—especially to women—and do it in partnership with ministries and global health agencies. When Nigeria convenes a cabinet-level conversation on malnutrition or vaccine coverage, Dangote’s philanthropic arm is typically in the room, not as a donor of the day but as a co-architect of delivery.

Johann Rupert — Michelangelo Foundation (South Africa/Global)

Focus: craftsmanship, cultural heritage, skills

Co-founded by South Africa’s luxury-goods magnate, the Michelangelo Foundation treats artisanal excellence as an economic and cultural asset worth safeguarding. The organization connects master artisans, designers and apprentices, mounting showcases and training programs that help endangered crafts compete with mass production. The logic here is developmental as much as aesthetic: preserve skills, build markets around them, and you support jobs and identity at the same time.

Nicky Oppenheimer — Brenthurst Foundation & Oppenheimer Memorial Trust (South Africa)

Focus: economic policy, governance; scholarships, research

The Oppenheimer family built mines; their foundations build ideas and talent. The Brenthurst Foundation operates like a compact think tank, publishing research and advising governments on growth, trade and security. Running in parallel, the Oppenheimer Memorial Trust underwrites scholarships and university research—steady, high-leverage bets that compound over decades. One shapes policy conversations; the other strengthens the bench of scholars and practitioners who carry those ideas into public life.

Nassef, Naguib & Samih Sawiris — Sawiris Foundation for Social Development (Egypt)

Focus: education, employability, poverty alleviation

Set up by Egypt’s most prominent business family, the Sawiris Foundation funds a broad pipeline: early-years learning and school improvement, scholarships at home and abroad, and job-creation programs that link training to actual hiring. It’s also active in rural development and women’s economic participation. The through-line is mobility—give people the skills and financing to move into higher-productivity work, and communities follow.

Abdul Samad Rabiu — ASR Africa (Nigeria/Pan-Africa)

Focus: tertiary education, health systems, social development

Rabiu’s foundation is designed for scale. It announces chunky, clearly costed grants—teaching hospitals, university infrastructure, diagnostics—and executes through local institutions. While Nigeria receives the largest share, ASR Africa writes checks beyond its home market, signaling a regional lens. The model is pragmatic: fund the asset, insist on transparency, and leave room for institutions to run their own programs rather than micromanaging from afar.

Mohamed & Yasseen Mansour — Mansour Foundation for Development (MFD) (Egypt)

Focus: healthcare access, education pathways, social protection

The Mansour Foundation works where public delivery is improving but still stretched: neonatal care units, primary-care upgrades, vocational training aligned to employer demand. A notable feature is its bias for partnerships with ministries and governorates—less “solo donor,” more co-financier. In practice that means government facilities end up stronger, not sidelined.

Patrice Motsepe — Motsepe Foundation (South Africa)

Focus: education, health, entrepreneurship, arts & culture

Among Africa’s earliest signatories to the Giving Pledge, Patrice and Precious Moloi-Motsepe back an unusually wide portfolio. Scholarships and school support sit alongside drought relief for farmers, funding for health emergencies and a steady stream of grants to sports, music and cultural programs. The bet is that social progress is braided: economic opportunity, resilience and cultural expression reinforce one another.

Mohammed Dewji — Mo Dewji Foundation (Tanzania)

Focus: education infrastructure, clean water, community health

Dewji’s foundation reads like a household-needs checklist: classrooms, boreholes, clinics, scholarships. The emphasis is local and visible; projects are designed to be counted in new desks and litres of clean water, not just in press releases. It’s philanthropy as municipal service delivery—close to the ground and easy to audit.

Michiel le Roux — Geleentheid Trust (South Africa)

Focus: bursaries, education innovation, social mobility

“Geleentheid” means “opportunity,” and the trust, founded by Michiel le Roux, the billionaire co-founder of Capitec Bank, stays true to the name. Its core business is financing studies for students who might otherwise stall after secondary school, plus support for programs that raise teaching quality and literacy. It’s quiet capital—few billboards, lots of transcripts changed.

Jannie Mouton — Jannie Mouton Foundation (South Africa)

Focus: education, research, entrepreneurship

Best known for building an investment empire, Mouton’s foundation targets the upstream drivers of growth: universities, research chairs, and early-stage entrepreneurship support. The work is patient and institution-focused—the kind that rarely trends on social media but shows up years later in start-ups formed, patents filed and graduates hired.

Strive & Tsitsi Masiyiwa — Higherlife Foundation (Zimbabwe/Region)

Focus: scholarships, leadership, health resilience

Higherlife is one of the continent’s longest-running structured philanthropies. Its scholarship programs have moved hundreds of thousands of students through secondary school and university. In parallel, the foundation funds leadership and digital-learning initiatives and has stepped into public-health gaps during emergencies. The philosophy is explicit: if human capital is Africa’s great advantage, then invest in it at scale.

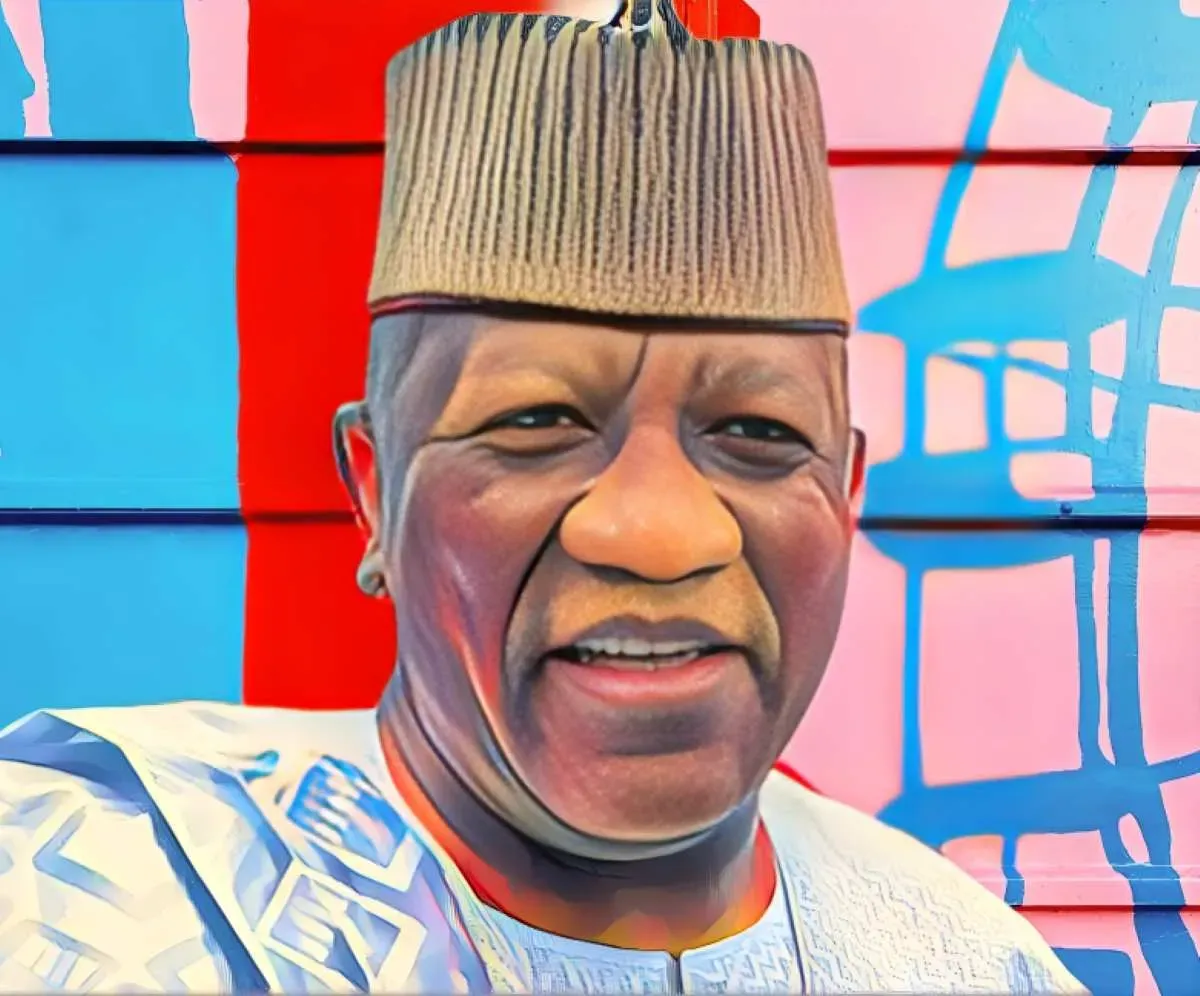

Theophilius Danjuma – TY Danjuma Foundation (Nigeria)

Focus: Scholarships, community health

The TY Danjuma Foundation was founded in 2009 by Nigerian billionaire, retired Lieutenant General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma with a $100 million endowment. Rather than channeling money into one-off campaigns, the TY Danjuma Foundation backs longer-term work by partnering with established NGOs and community groups. Its annual grant program funds priority areas such as health and education, while a pool of discretionary money is kept aside for emergency responses. One of its most visible achievements is the Rufkatu Danjuma Maternity Centre in Takum, Taraba State, which was built with Development Africa. The facility was designed to tackle the high rates of maternal and child mortality in the region and today provides critical health services for families who previously had little access to care.

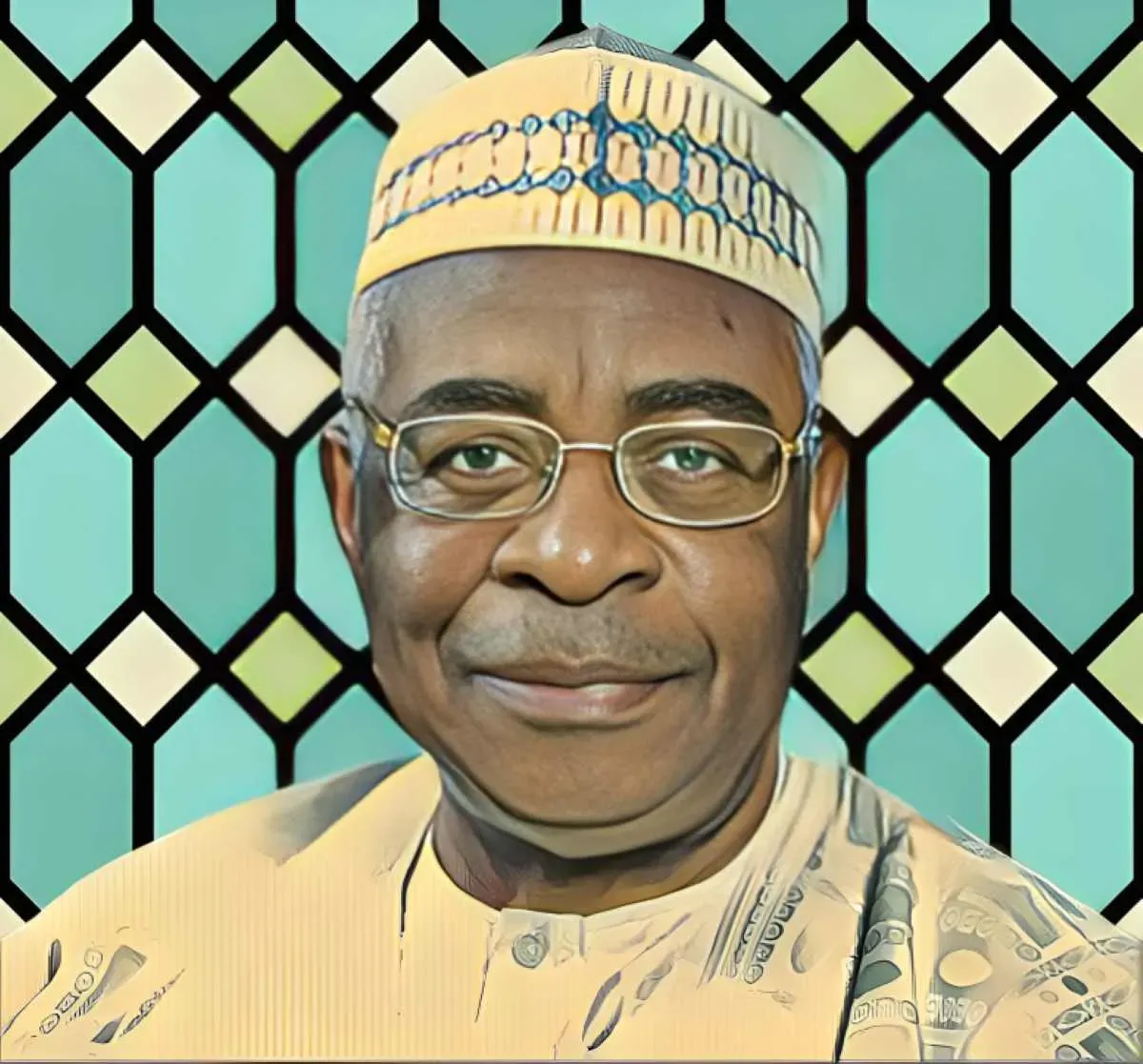

Mohammed Ibrahim – Mo Ibrahim Foundation (Africa)

Focus: African governance

The Mo Ibrahim Foundation was set up to encourage better governance and stronger leadership across Africa. At the heart of its work is the idea that progress requires accountability, data, and leaders who put public service ahead of personal gain. The foundation publishes the Ibrahim Index of African Governance has become the foundation’s signature contribution, offering a detailed look at how countries perform on issues from security to economic opportunity. The index is widely used by policymakers, academics and civil society groups as a way to measure progress—or the lack of it—across the continent. The foundation also hands out one of Africa’s most prestigious awards, the Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership. The honor goes to former heads of state who left office with their record intact and their democratic institutions stronger.