Table of Contents

Nigeria’s biggest names in the electricity business are quietly preparing for what could be their most significant cash injection in years. The federal government has struck a deal with power generation companies to settle a staggering ₦4 trillion ($2.7 billion) in unpaid bills—a crippling backlog that has hobbled investment and limited how much power these plants can actually produce.

For Femi Otedola, the billionaire who controls Geregu Power Plc, the announcement is a major turning point. Geregu runs the Geregu I gas plant in Ajaokuta, Kogi State, with an installed capacity of about 435 megawatts. The company has consistently been among the most commercially stable GenCos in the country, but it has been starved of timely payments from the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading (NBET), the government-controlled manager and administrator of the electricity pool. The settlement plan gives it a cleaner balance sheet and a clear runway to pursue long-stalled investments.

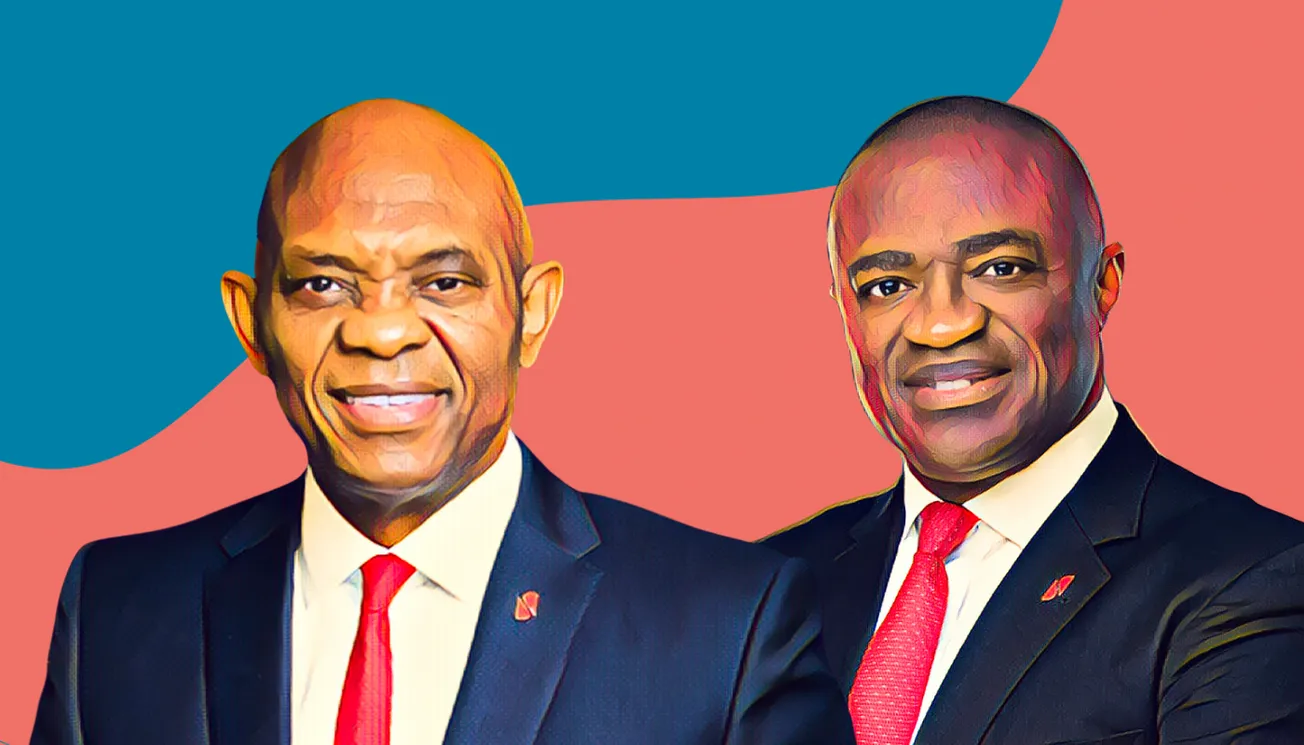

Tony Elumelu, another titan of the power sector, has even more at stake. Through Transcorp, he controls two massive thermal assets: the 972MW Ughelli Power Plant in Delta State and the Afam I–V and Afam III Fast Power units in Rivers State, which together have around 966MW of installed capacity. Ughelli is the country’s largest single gas-fired plant, and Afam has been at the heart of the government’s drive to stabilize power supply in the South-South. But for years, both plants have run below potential because they simply haven’t been paid in full for the electricity they supply. Turbine overhauls have been delayed, expansion projects shelved, and operational costs pushed to the edge. A functioning payment pipeline could change all of that almost overnight.

Deji Adeleke’s Pacific Energy faces a similar reality. The group owns the Omotosho and Olorunsogo Phase I plants—both in the 300 to 336MW range—alongside a newly completed 1,250MW station at Omotosho that has been unable to come online fully because of weak gas financing and grid constraints. With the debt backlog gone and payment assurances strengthened, Pacific Energy could finally tie into its gas infrastructure and bring thousands of megawatts closer to the grid.

No less impacted is Tope Shonubi, the co-founder of Sahara Group, which operates Egbin Power. Egbin’s 1,320MW plant on the Lagos Lagoon is the single largest power station in Nigeria, yet it has been forced to stagger maintenance schedules and hold back on upgrades. Sahara has long said that market liquidity, not technology, is the real choke point. Consistent payment from the grid operator would allow Egbin to fully utilize its six 220MW units and restore capacity that’s been offline for years.

On the hydro side, Tunde Afolabi’s Mainstream Energy controls Kainji and Jebba, two of Nigeria’s oldest and most important hydropower dams. Together, they have about 1,338MW of installed capacity. Mainstream has managed to bring many of the old turbines back to life through rehabilitation programs, but funding gaps caused by unpaid invoices have repeatedly slowed those efforts. A more predictable payment structure would give Mainstream the flexibility to deepen those refurbishments and stabilize power generation from Nigeria’s main river backbone.

This debt crisis is not new. For years, GenCos have been supplying electricity without being paid in full, leading to a vicious cycle: late payments mean gas suppliers cut back, turbines are run to their limits, planned maintenance gets postponed, and plants underperform. Official figures show that average available generation is often far below installed capacity—not because Nigeria lacks power stations, but because those stations are operating on shoestring finances.

The government’s new plan involves issuing bonds and negotiating bilateral settlements to cover the verified debts. If executed properly, it will be the single largest financial clean-up in the power sector since privatization. More importantly, it could restore credibility to a market that has bled investor confidence for nearly a decade.

Still, challenges remain. New arrears could easily pile up again if tariffs, subsidies and distribution losses remain misaligned with the actual cost of power. But for now, for Nigeria’s most powerful electricity players—Otedola, Elumelu, Adeleke, Shonubi and Afolabi—the winds have shifted. For the first time in years, they can plan on getting paid. And if they do, the country’s grid might finally see some of the megawatts it’s been promised for so long.