Table of Contents

Cameroon’s long running political drama has acquired a new back channel, with businessman Baba Ahmadou Danpullo cast as an informal go between for President Paul Biya and his estranged former ally turned rival, Issa Tchiroma Bakary.

The mediation effort lands in the wake of the October 12 presidential election, a contest that set off weeks of uncertainty and street anger after Tchiroma declared victory and challenged the official count. Biya, 92, was declared the winner by the Constitutional Council, and clashes that followed prompted reports of deaths and mass detentions from civil society and the United Nations.

Tchiroma’s break with the establishment was abrupt. He resigned from government in June 2025 and launched a presidential bid within a day, seeking to harness northern frustration with Yaounde and the sense that the presidency had become distant and inaccessible. After the vote, tensions escalated around his stronghold of Garoua, and he later surfaced in The Gambia, where officials said he was being hosted temporarily on humanitarian grounds and for his security.

It is in that fragile space that Danpullo steps in. Reporting by Jeune Afrique said the businessman has often played a decisive behind the scenes role in Tchiroma’s political trajectory and has now been positioned as a mediator to soften the standoff with the presidency.

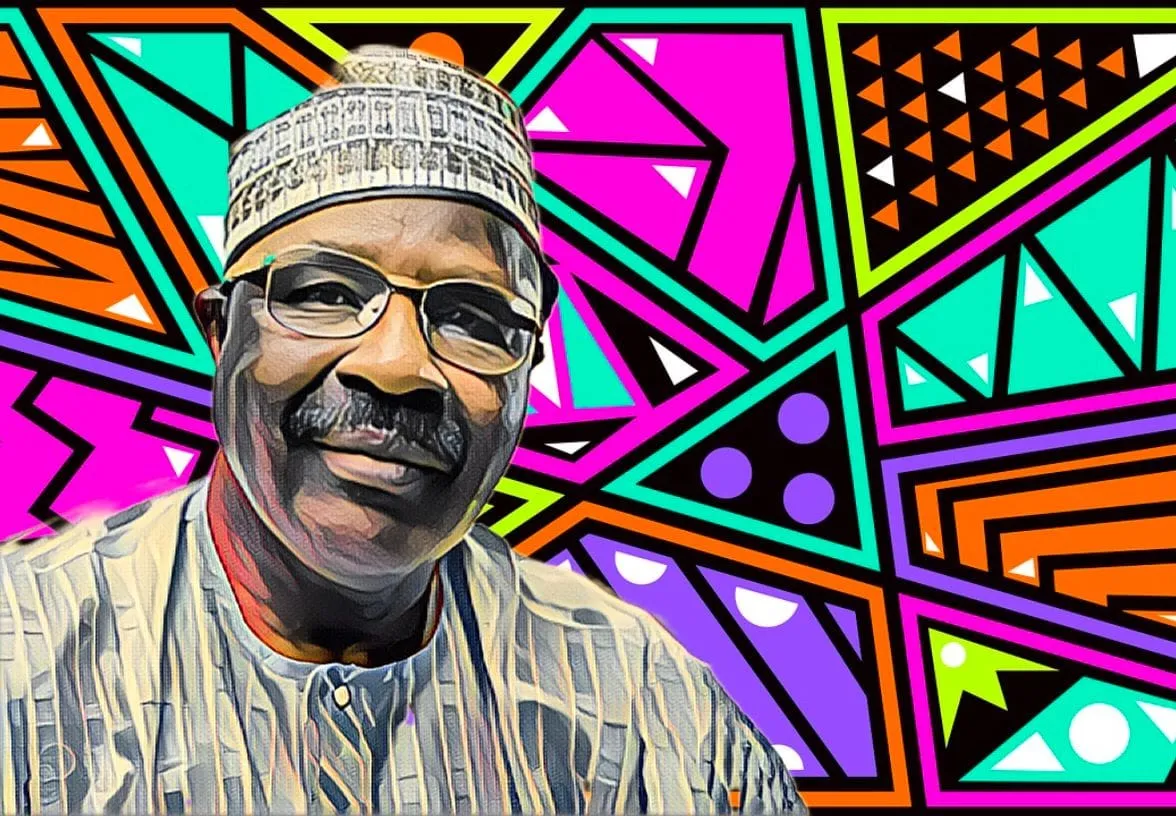

Danpullo is not a typical political fixer. He is Cameroon's wealthiest and most popular business leader with commercial interests across Africa that span tea production, telecoms and real estate.

In Yaounde, the logic is plain enough. A hard political negotiation with Tchiroma risks inflaming a volatile situation, particularly in the north, where the ruling coalition has long relied on carefully balanced alliances. An intermediary who can speak to both sides, and who is not formally part of the state apparatus, can offer each camp a way to explore options without appearing to retreat.

The question is what either side wants. Biya’s circle is focused on stabilising the aftermath, containing dissent and preventing the appearance of a split inside the security services. Tchiroma, meanwhile, has shown he can mobilise anger quickly and create disruption, including calls for civil resistance and work stoppages as protests against the declared result.

Even so, mediation in Cameroon has a familiar rhythm. Deals are rarely signed in public. They are felt first in small shifts: a softened tone, a quiet travel permission, a meeting that happens without fanfare. The added twist is Danpullo’s commercial weight. When a mediator is also a major investor, his incentives can align neatly with de escalation, because instability is bad for business, capital and cross border banking.

This is not a clean story of reconciliation. It is a test of whether Cameroon’s system still has enough elasticity to absorb a rupture from within its own ranks. Tchiroma is not a classic opposition outsider. He spent years as a government minister and spokesman, defending the administration he now attacks.

Whether Danpullo can pull both men toward a workable pause will depend on what is on the table, and what each side can sell to its supporters. Cameroon’s post election nerves have not settled yet, and quiet diplomacy may be the only form of politics that still moves safely in public.