Table of Contents

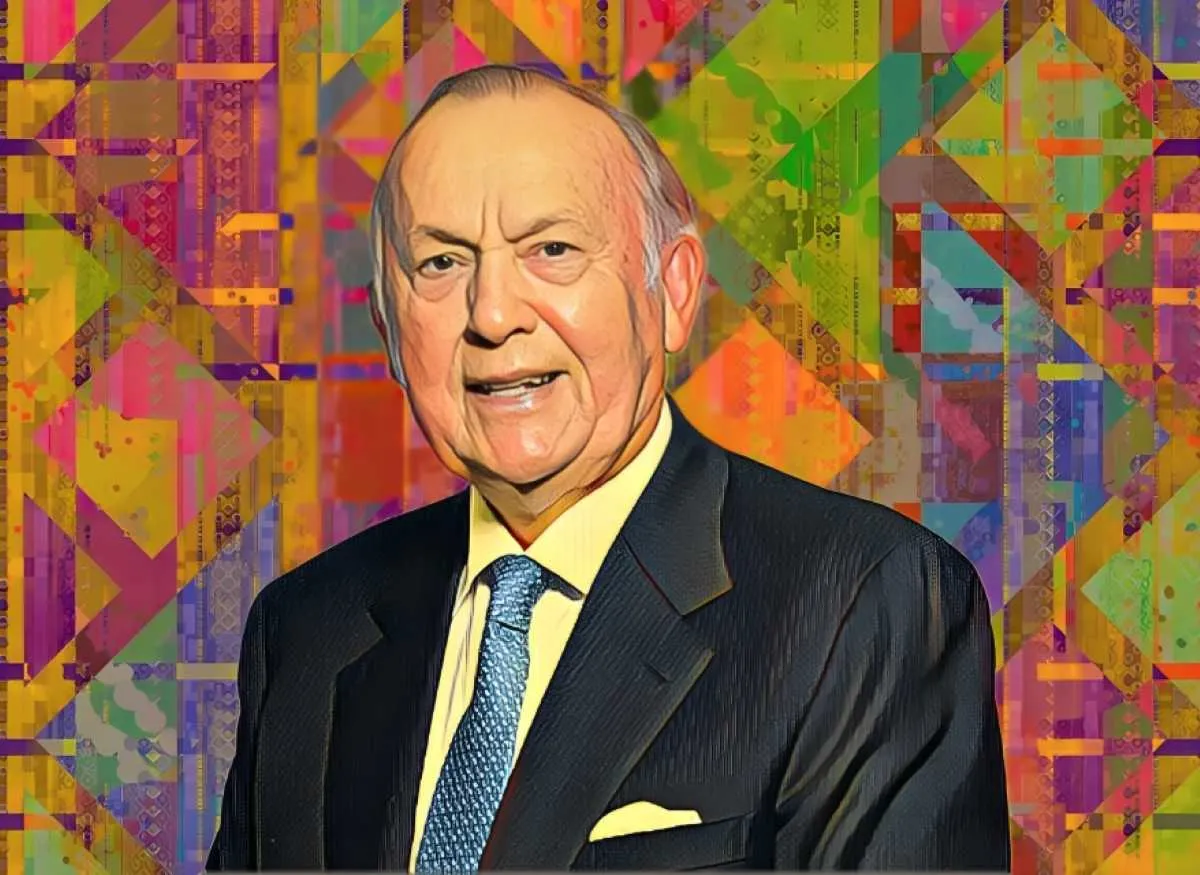

Lakshmi Mittal, the steel tycoon who built ArcelorMittal into the world’s largest steelmaker, is again weighing a deal to step away from South Africa’s struggling steel business, reopening negotiations with a state backed lender after months of deadlock.

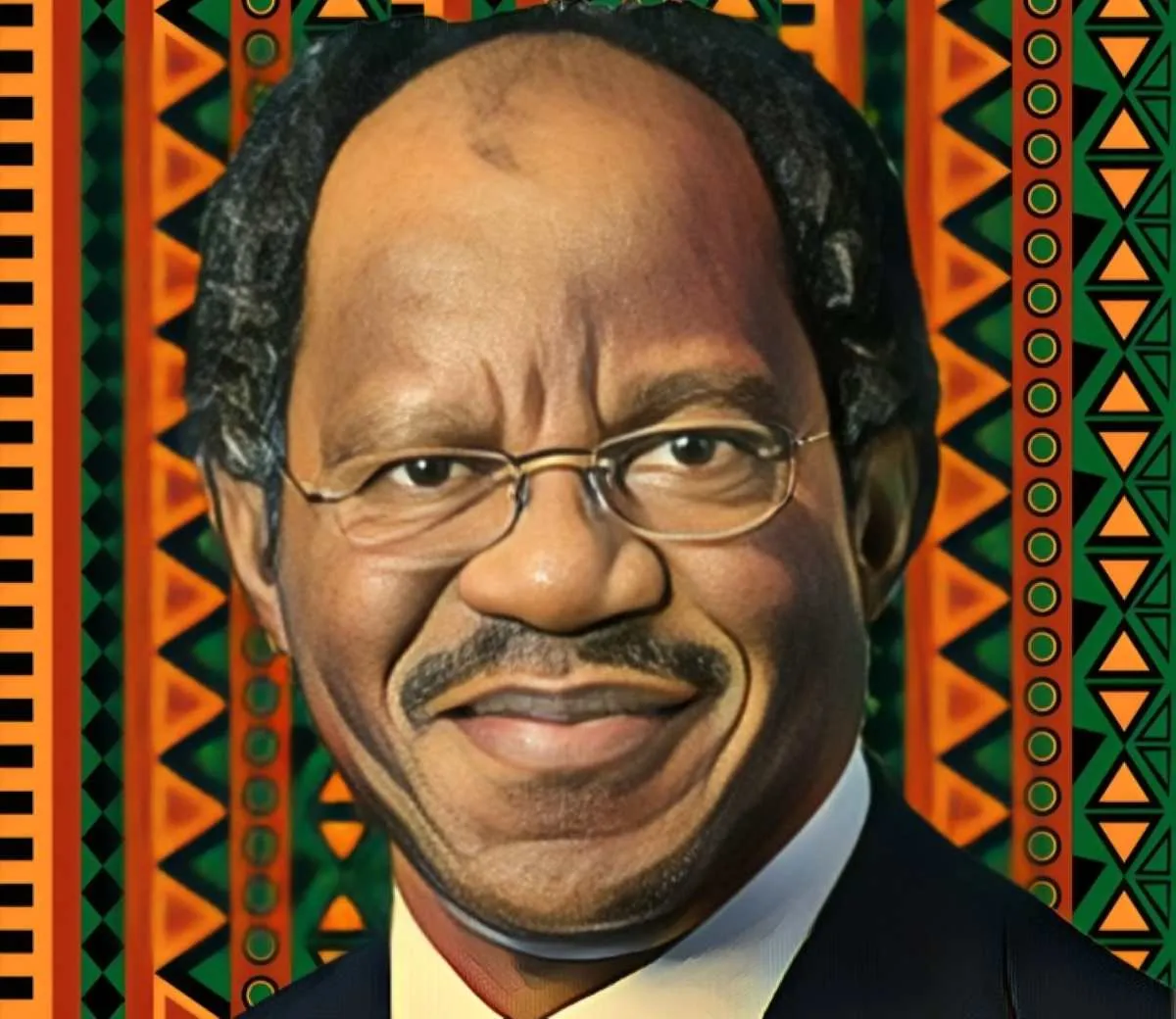

ArcelorMittal South Africa said it is in advanced discussions with the Industrial Development Corporation, known as the IDC, on a potential transaction based on a non binding term sheet. The company cautioned there was no certainty a deal would be struck.

The talks put Mittal at the centre of a political and industrial dilemma. South Africa’s government wants to protect local steel capacity and jobs tied to construction, mining and manufacturing. ArcelorMittal, meanwhile, has been trying to stop losses in a market squeezed by weak demand, high electricity costs, logistics failures and competition from scrap based mini mills and imported steel.

ArcelorMittal South Africa is a listed company but its fortunes are closely tied to the Luxembourg based parent led by Mittal. The South African unit has been under pressure for years, and last year it mothballed parts of its long steel operations as it sought to stem losses.

At stake is the future of facilities in Newcastle and Vereeniging, which produce long steel products such as reinforcing bar and wire rod used in building projects. Plans to close and wind down those operations put about 3,500 jobs at risk, and a union later warned retrenchments could rise above 4,000 when broader cuts are counted.

The IDC is not a new player in the saga. It is the company’s second largest shareholder, with an 8.2 percent stake, and it has provided significant financial support over the past two years to keep the business operating. That support totals about 2.6 billion rand, or roughly $161 million, a lifeline that bought time but did not fix the economics.

Earlier talks between ArcelorMittal and the IDC ended without a deal in late 2025, leaving the steelmaker free to look for other investors. The collapse underscored a familiar problem in state rescues: the price and structure have to satisfy taxpayers and workers, while also giving the seller a clean exit and limiting future liabilities.

Reporting linked to the renewed negotiations has pointed to an offer that previously failed to win ArcelorMittal’s support. A proposal discussed publicly late last year was valued at about 8.5 billion rand and would have included repayment of debt owed to the parent company, according to market reports.

ArcelorMittal South Africa’s announcement sparked a sharp market response. Its shares jumped on the news, a sign that investors see value in any outcome that brings clarity after years of uncertainty about plant closures and the company’s ability to fund operations.

The broader context is grim. South Africa’s steel industry has been battered by power shortages, higher input costs and chronic rail and port bottlenecks that make it harder to move raw materials in and finished product out. At the same time, imports have challenged local producers on price.

Mittal’s group has argued that without a workable policy and infrastructure environment, keeping loss making capacity open becomes hard to justify. ArcelorMittal South Africa has previously sought relief measures such as stronger import protections and lower cost logistics, and it has repeatedly warned that delays in reaching a sustainable solution would push it closer to shutdown.