Table of Contents

The Woman Before the Scandal

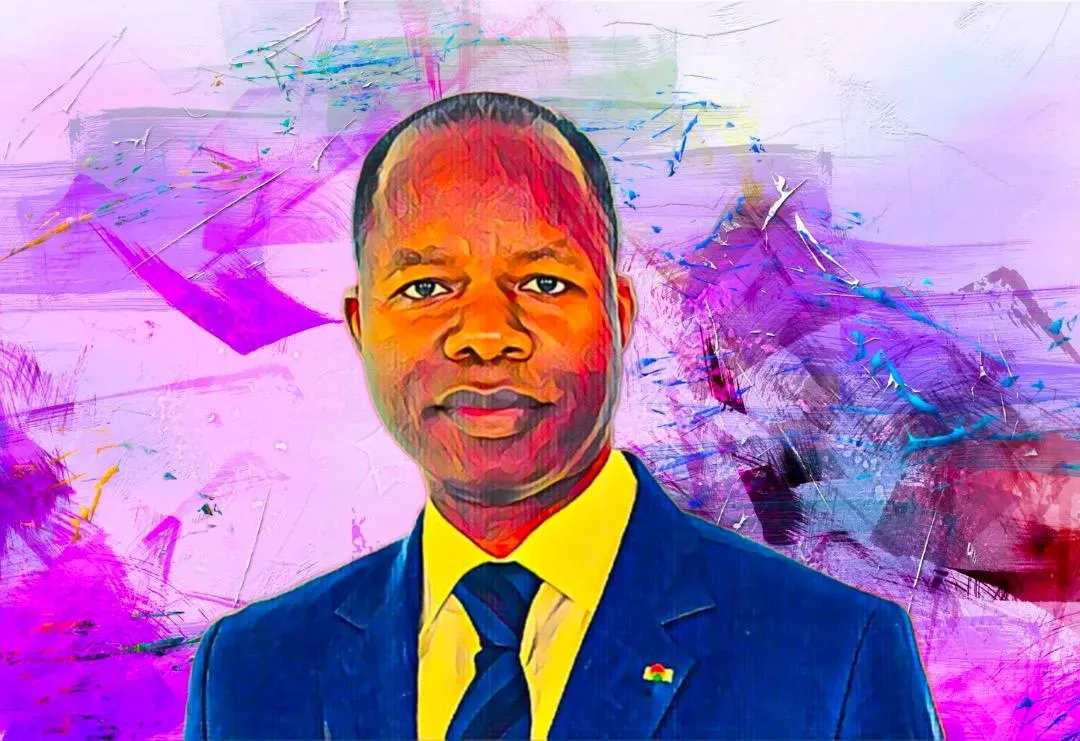

Nigeria’s former minister of petroleum resources, Diezani Alison-Madueke, is currently on trial at Southwark Crown Court in London on a raft of bribery charges that have turned her name into global shorthand for Nigerian corruption. British prosecutors allege that she accepted cash, luxury goods, and access to high-end London properties from oil industry figures who hoped she would use her influence over Nigeria’s state-owned oil companies in their favour—allegations she firmly denies.

Yet before Alison-Madueke became a permanent fixture in corruption headlines, she was something else entirely: a trailblazer in one of the world’s most male-dominated industries. She did not stumble into power; she built it over decades in the global oil business, beginning at Shell Petroleum Development Company in Nigeria and rising in a corporate culture where women—and especially African women—were almost invisible at senior level. By 2006, she had broken a major barrier, becoming Shell Nigeria’s first female executive director, a role that placed her among the most powerful energy executives on the continent and set the stage for her subsequent leap into ministerial office and, eventually, the presidency of OPEC in 2014.

As president of OPEC, she led an organization that shaped global oil prices and energy policy. She represented Nigeria at international forums, negotiated with other oil-producing nations, and operated at the highest levels of global energy politics. Whatever criticisms might be leveled at her tenure, no one disputes that she occupied positions of genuine power and influence, earned through a career that spanned decades in both the private and public sectors.

Her trajectory didn’t stop there. She moved into government, serving as Minister of Transport, then Minister of Mines and Steel Development, before being appointed Minister of Petroleum Resources in 2010—a position that made her one of the most powerful figures in Nigerian politics and global energy markets. For a country where oil revenues account for the vast majority of government income and foreign exchange, the petroleum minister isn’t just another cabinet position. It effectively controls the nation’s economic lifeline.

This context matters because the current narrative has largely erased it. The woman now reduced to tabloid stories about shopping sprees and luxury goods was, for most of her professional life, a serious player in global energy politics—someone who had earned her place at tables where few Nigerian women, and few women anywhere, were invited to sit.

Understanding who she was makes it possible to ask harder questions about what she’s accused of, how those accusations are being presented, and why the gap between the legal case and the public narrative has become so wide.

The Anatomy of a Witch Hunt

The pattern of misinformation around Diezani Alison-Madueke didn’t start with this trial. It’s been building for years, and it follows a consistent playbook: sensational claims that spread rapidly, generate outrage, and then—sometimes months or years later—turn out to be exaggerated, misleading, or entirely false.

The Diamond Bra That Never Existed

Start with the most instructive example: the diamond bra. In early 2021, as Nigeria grappled with security crises, economic hardship, and rising public anger at government failures, a story exploded across Nigerian media and social platforms. The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), outlets reported, had recovered a $12.5 million diamond-encrusted bra from Diezani’s apartment during their investigation.

Twelve point five million dollars. On a bra. Diamonds encrusting lingerie while ordinary Nigerians struggled to survive.

The story was perfect. It was visceral, gendered, excessive in exactly the right way to generate maximum disgust. It painted a picture of corruption so grotesque, so personally decadent, that it became the defining image of her alleged crimes for millions of Nigerians. It was also completely false.

In November 2021—after the story had circulated for months, after it had shaped public opinion and become embedded in the collective understanding of her corruption—EFCC Chairman Abdulrasheed Bawa publicly admitted the truth: there was no diamond bra. It had never been recovered. The entire story was a fabrication that had originated on social media and been amplified by media outlets that never bothered to verify it.

Fact-checkers had already debunked it, but the correction received a fraction of the attention the original lie had generated. By the time the truth came out, the damage was done. The image of the diamond bra—corrupt, excessive, obscenely feminine—had already become part of the permanent record of public perception.

This wasn’t a simple mistake. It was a lie that was allowed to run wild because it served a purpose: it kept Diezani at the center of corruption discourse at a moment when the government needed a distraction from its own failures.

The £2 Million Harrods Story: History Repeating

Now, in January 2026, we’re watching the same pattern play out again—this time in a London courtroom. Headlines screamed that Diezani had “spent” or “blown” £2 million at Harrods. She had “run out of space for luxury goods.” She had enjoyed Harrods’ exclusive personal shopping service, living a life of such excess that even London’s most famous luxury retailer couldn’t contain her appetite. It’s the diamond bra story all over again: spectacular, damning, perfectly calibrated to generate outrage.

But here’s what the court actually heard, according to the prosecution’s own opening statement: Payment cards linked to Kolawole Aluko and his company, Tenka, were used to charge more than £2 million at Harrods. The prosecution asks the jury to infer that these purchases were “for” Diezani Alison-Madueke.

Notice what’s missing: any proof that she personally spent this money. Any itemized record showing these purchases ended up in her possession rather than with Aluko, his family, his associates, or the various people in his orbit. Any evidence beyond the prosecution’s invitation to infer, to assume, to conclude that because Aluko had business interests connected to her position, everything he spent must have been for her.

The headlines transformed “cards linked to Aluko charged £2 million, allegedly for purchases intended for Alison-Madueke” into “Diezani spent £2 million at Harrods.” The careful legal language of inference became the declarative certainty of fact. And once again, the most viral detail in a corruption case turned out to be, at minimum, a significant oversimplification of what prosecutors can actually prove.

Watch the transformation:

- What prosecutors said: “More than £2m spent at Harrods for Alison-Madueke”

- What headlines said: “Diezani spent £2m at Harrods”

- What social media said: “Diezani blew £2m at Harrods and ran out of space for luxury goods”

Each iteration adds certainty, adds color, adds moral clarity—and moves further from what can actually be proven.

The Properties and Jets: Another Layer of Distortion

The pattern continues with virtually every element of the case. The prosecution alleges she received benefits including “high-end London properties.” But she never owned these properties. She had use of them—essentially an extended, very expensive Airbnb arrangement. The properties were owned by others; she lived in them temporarily.

The private jets? Also not hers. She had access to them, the way any minister being courted by wealthy contractors and businessmen might. But “she had temporary use of properties owned by businessmen with interests before her ministry” doesn’t have the same ring as “luxury Knightsbridge properties and private jets.”

So the coverage defaults to the more spectacular version, even though it’s misleading. Even though it suggests a level of personal enrichment—actual ownership of assets—that isn’t what’s being alleged.

Why This Pattern Matters

This isn’t about defending Diezani Alison-Madueke. It’s about recognizing that when the most prominent details in a corruption case—the diamond bra, the £2 million shopping spree, the “luxury properties”—all turn out to be exaggerated, misleading, or in one case entirely invented, we should ask harder questions about everything else we’ve been told.

If they got the diamond bra completely wrong, and they’re getting the Harrods story substantially wrong, and they’re mischaracterizing the properties and jets, what else in this narrative is distorted?

More importantly: who benefits from these distortions? Why does the story consistently get inflated in ways that make it more sensational, more certain, more morally clear-cut than the actual evidence supports?

The answer is uncomfortable: sensational stories about corrupt African politicians serve everyone’s interests except the truth. They give media outlets clicks and engagement. They give Western governments a way to demonstrate their anti-corruption credentials. They give Nigerian officials a convenient scapegoat to distract from current failures. And they give the public a simple villain in a complex story about systemic corruption.

But they don’t serve justice. And they don’t serve accuracy.

What’s Actually on Trial

With that pattern established, we can now examine what Diezani Alison-Madueke actually stands accused of—and the significant gap between the legal substance and the public perception.

The Charges: Benefits, Not Bribes-for-Contracts

She faces five counts under the UK Bribery Act of accepting “financial and other advantages” from five men: Kolawole Aluko, Olajide Omokore, Benedict Peters, Igho Sanomi, and Kevin Okyere. These men controlled companies that did lucrative business with Nigeria’s state oil entities—NNPC, NPDC, and PPMC—which Alison-Madueke, as petroleum minister, effectively controlled.

The alleged benefits include: use of high-end London properties (not ownership), refurbishments to those properties, staff to maintain them, luxury shopping, use of private jets, and cash payments. Additional counts involve allegations that benefits were channeled through intermediaries including Doye Agama and his church, and that she accepted bribes from Olatimbo Ayinde while Ayinde’s firms held PPMC contracts.

But here’s the detail that fundamentally changes how we should understand this case:

The prosecution explicitly states they have no evidence that any particular oil or gas contract was wrongly awarded as a result of these alleged benefits.

Read that again. They’re not alleging she sold specific contracts in exchange for specific bribes. They’re not claiming that Aluko or Peters or any of the others got deals they shouldn’t have gotten because they paid her off. They’re not saying Nigeria’s oil blocks were auctioned to the highest bidder in some corrupt bargain.

What they’re alleging is more nebulous: that given her position, she shouldn’t have accepted these benefits from people doing business with entities she controlled, regardless of whether those benefits influenced any specific decision. The impropriety is in the pattern and the appearance, not in any demonstrable quid pro quo.

This is a legally and morally significant distinction. The jury isn’t being asked, “Did she sell this contract for that bribe?” They’re being asked something far more ambiguous: “Do you believe these benefits were given and received with corrupt intent, even if we can’t show you what specific improper act resulted?”

The Evidentiary Challenge: Proving Invisible Intent

This is where the case becomes genuinely difficult, because intent is invisible. You can show that someone received money, property, or services. You can demonstrate that the people providing those things had business interests that could benefit from the recipient’s position. You can establish a timeline that looks suspicious. But proving that both parties understood the exchange as corrupt—that benefits were given to induce improper performance, and were accepted with that understanding—requires evidence that rarely exists outside of extraordinarily careless criminals.

There are no emails saying “here’s £500,000 for that oil block.” No recorded calls trading contracts for cash. No smoking-gun document where Alison-Madueke promises favorable treatment in exchange for benefits.

What the prosecution has is pattern and inference. They have the luxury, the timing, the relationships, the business connections. They have Aluko’s cards at Harrods and his properties in Knightsbridge. They have private jets and expensive gifts and the circumstantial architecture of what could be—what they believe must be—corruption.

The defense’s counter is predictable but not unreasonable: these were long-standing personal and professional relationships in a small, elite industry. Hospitality and gift-giving are cultural norms, not criminal conspiracies. Without explicit evidence of a corrupt bargain, you’re criminalizing the normal texture of how powerful people interact.

Both positions have merit. That’s what makes this a genuinely difficult case—one that should be decided by a jury weighing evidence, not by a public that’s already made up its mind based on exaggerated headlines.

When Lobbying Becomes Bribery: The Cultural Double Standard

To understand why this case is so complex, you need to understand how power works in the global oil industry—and in elite politics everywhere.

At Alison-Madueke’s level of power, you don’t just make decisions—you live inside an ecosystem of influence. Traders want access. Contractors want favor. Financiers want information. And everyone wants to build relationships with people who control billions in contracts and concessions.

This lobbying takes familiar forms everywhere: dinners at exclusive restaurants, invitations to private boxes at events, use of corporate jets, strategic donations to favored causes. It’s how elite networks function globally. The difference is that in London and Washington, this influence-peddling has been professionalized, regulated, and declared legal within certain bounds. There are lobbyist registries and disclosure requirements that supposedly keep it on the right side of corruption.

But strip away the bureaucratic superstructure and you’re left with the same fundamental exchange: access, hospitality, and strategic generosity flowing from those who want favors to those who can grant them.

The Nigerian version isn’t structurally different from the Western version. It’s just that when Nigerian elites do it, we call it corruption. When Western elites do it, we call it networking.

This isn’t to excuse genuine corruption. If the prosecution is right about the scale of what Alison-Madueke accepted, it crosses any reasonable line. But it does raise an uncomfortable question: Would a forensic examination of any American or British energy secretary’s lifestyle reveal similar patterns of corporate-funded hospitality, travel, and luxury that, viewed with sufficient suspicion, could be reframed as corrupt benefits?

Or is there a double standard at work—one that treats as criminal in Nigeria what would be dismissed as “just how business works” in London or Washington?

A Trial in the Wrong Country?

There’s something peculiar about watching a Nigerian former minister stand trial for corruption in a British court while Nigeria itself has been unable or unwilling to bring her home.

The EFCC has had years to prosecute Alison-Madueke domestically. Multiple extradition requests have been made but have failed or been inadequately pursued. When she applied to Nigerian courts to join proceedings there, judges dismissed her applications as “ploys to evade justice in the UK”—creating a bizarre Catch-22 where she can’t come home to face charges because courts won’t allow it, but her absence is then cited as proof of guilt.

Meanwhile, Britain—which spent decades facilitating the flow of questionable wealth from Nigeria into London property, British banks, and yes, Harrods—has discovered a sudden enthusiasm for prosecuting the corruption it once happily enabled.

Why now? Why this case? Why in London rather than Lagos?

The generous interpretation: the UK Bribery Act gives British prosecutors tools and jurisdiction that Nigerian authorities lack, and Britain has a legitimate interest in demonstrating that its territory isn’t a safe haven for corrupt proceeds.

The cynical interpretation: post-Brexit Britain needs to showcase its anti-corruption credentials, and what better way than a high-profile prosecution of a notorious foreign official? It sends a message, reassures international partners, and makes for spectacular headlines—all while avoiding the messy reality that Nigeria’s own institutions remain unable to deliver justice domestically.

The trial actually might serve British interests more than Nigerian ones. It allows Britain to perform anti-corruption virtue while Nigeria’s institutions remain dysfunctional. And it raises a basic question: Is this the best use of UK resources—prosecuting a foreign ex-minister for accepting hospitality and gifts, when the country she allegedly harmed hasn’t managed to bring her home for trial?

The Gendered Spectacle

It’s impossible to ignore what makes Diezani Alison-Madueke such a perfect villain for this narrative: she’s a woman.

When male politicians face corruption allegations, coverage focuses on mechanics—contracts, companies, financial flows. When women face similar allegations, we get shopping sprees, jewelry, and interior decoration. Her spending gets read as frivolous in ways a man’s spending wouldn’t.

The diamond bra story—entirely fabricated—worked precisely because it was gendered, sexualized, spectacular. It painted her corruption as excessively, almost pornographically feminine. Diamonds on her body. Luxury goods she couldn’t contain. The corruption of a woman reduced to consumption and vanity.

And she’s no longer in power, which makes her a safe target. There’s no diplomatic fallout from prosecuting her, no powerful constituency to defend her, no risk of retaliation.

She is, in short, the perfect defendant: high-profile enough to generate headlines, powerless enough to be prosecuted without consequence, female enough to be reduced to shopping and vanity, African enough to confirm existing stereotypes.

When the Story Sells Itself

There’s a reason the Harrods detail dominates coverage: it’s perfect for headlines. Harrods is a globally recognized symbol of luxury and elite consumption. Everyone knows Harrods. When you attach it to corruption allegations, it does narrative work that “accepted cash payments” can’t match. Private jets and Knightsbridge properties work the same way. These details are visual, tangible, morally clarifying. They make corruption feel real in a way that complex financial arrangements don’t.

Complex stories about systemic lobbying, ambiguous hospitality, and circumstantial evidence don’t generate clicks. Simple stories about a corrupt minister “blowing” £2 million at Harrods? Those sell themselves.

The result: she had use of properties (like an expensive Airbnb), but coverage implies she owned Knightsbridge mansions. She had access to private jets, but coverage suggests they were hers. What prosecutors carefully describe as benefits that “may have been intended to induce improper performance” becomes, in headlines, straightforward bribery. Inference becomes fact. Questions become certainties.

Diezani Alison-Madueke has been convicted in the court of public opinion on evidence that would make any serious legal analyst uncomfortable. And the mechanism of that conviction is precisely the pattern we’ve traced: each retelling adds certainty, each headline strips nuance, until what remains is caricature rather than case.

The Real Question

Diezani Alison-Madueke will be judged by a jury that has heard actual evidence and been instructed to apply actual legal standards. That jury will decide—based on what was proven in court, not claimed in headlines—whether she accepted benefits with corrupt intent.

The rest of us have made up our minds based on a narrative that confirms what we believe about power, corruption, and excess. That narrative is demonstrably detached from reality. She didn’t own properties—she used them. She didn’t own jets—she had access. She didn’t personally spend £2 million—cards linked to someone else were used for purchases allegedly intended for her. And one of the most damning stories—the diamond bra—never happened at all.

These distinctions matter. They’re the difference between evidence and assumption, between what happened and what makes a good story.

The next time you see a corruption allegation reduced to one viral number and a shopping-spree headline, ask: What’s being simplified?

What’s being exaggerated? Whose interests does that serve?

The most corrupt thing about corruption stories is often the way they’re told. And once you see that pattern, you can’t unsee it.

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on Leaders.ng.