Table of Contents

A top South African investment manager is warning that the rush into artificial intelligence is starting to look like a bubble, with companies leaning on the buzzword to justify soaring valuations and investors piling in before the business basics are proven.

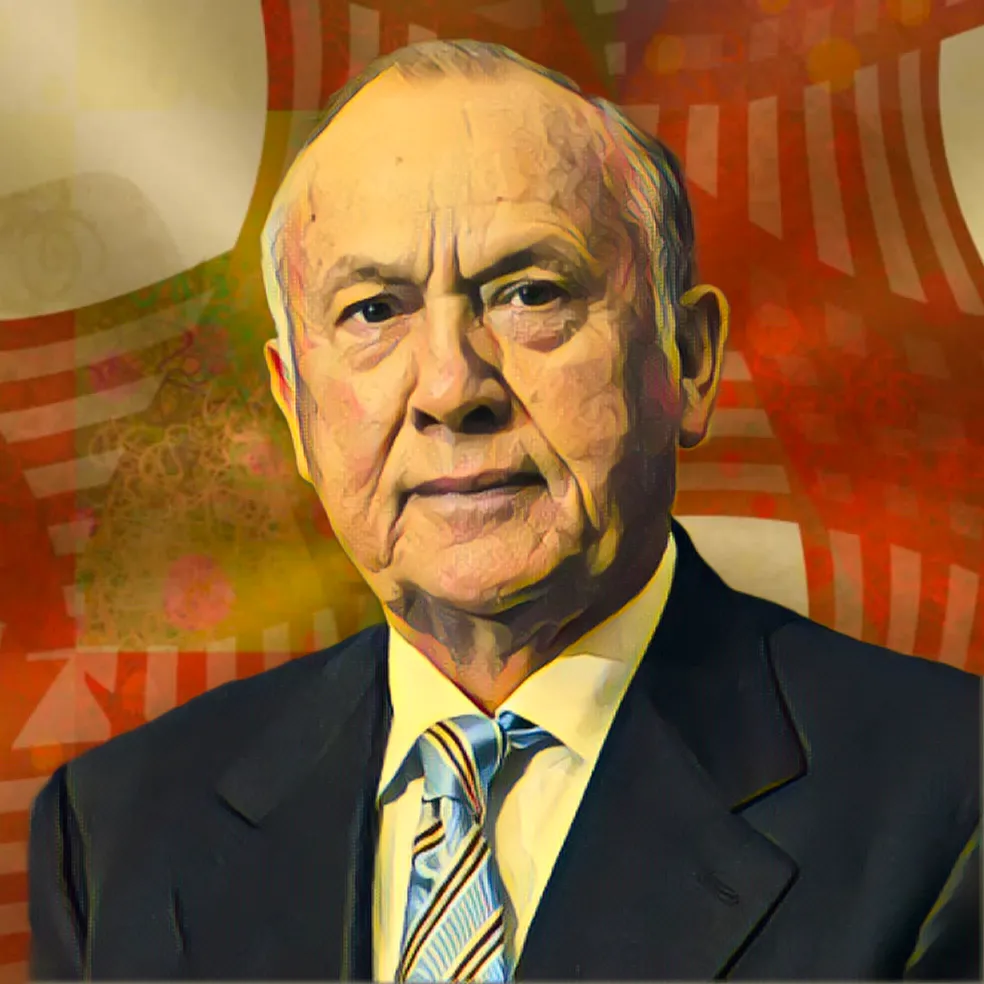

Thato Ntseare, an investment manager at E Squared Investments, says South Africa needs clearer governance guardrails for AI focused funding so that a market correction does not wash out smaller investors and weaken confidence in the country’s tech sector.

In an interview carried by Business Times, Ntseare said there is “big talk” that AI investment is mimicking “a bit of a bubble.” His central complaint is not that AI lacks potential, but that much of what is being sold as AI is packaging rather than substance.

Ntseare said many firms are “wrapping” ordinary products in an AI story. Instead of building their own models or tools, they adopt existing technologies and rebrand them. The pitch works, he argued, because investors are rewarding anything that sounds like AI, often without asking whether the solution is native to the company or defensible in the market.

“There is a lot of hype around these businesses,” Ntseare said, adding that a simple claim of using AI can attract valuations in the billions of dollars.

His caution lands at a time when global spending projections are growing rapidly. The Financial Times has reported that AI related spending could exceed $660 billion in 2026, a scale that dwarfs many national economies and raises questions about how long the investment cycle can remain as aggressive as it is.

Markets have also shown signs of strain. In the past week, shares of major United States technology companies that have poured money into AI fell sharply, including Amazon, Microsoft, Nvidia, Oracle, Meta Platforms and Alphabet. FactSet data cited by MyBroadband said those firms lost more than $1 trillion in combined market value on one day of trading.

Nvidia, the clearest stock market winner of the AI boom because of its dominance in processing chips, also faced fresh scrutiny after its chief executive, Jensen Huang, tried to cool expectations around a widely discussed funding plan linked to OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT. Huang told reporters that a planned investment of up to $100 billion to support new data centres and AI infrastructure was never a commitment. A Wall Street Journal report said the plan had stalled, and sources told the paper Huang had expressed concerns about OpenAI’s business discipline, claims he later dismissed.

The wobble has revived comparisons to the dotcom era, when hype outpaced revenue and easy money floated weak companies. Some analysts argue today’s cycle is different. JP Morgan investment specialist Stephanie Aliaga has said much of the current buildout is funded by free cash flow from companies with strong balance sheets, unlike the 1990s, when many firms had limited profitability and relied heavily on external capital.

Aliaga has also argued that AI revenue is scaling alongside investment, pointing to increased cloud demand and productivity gains in areas such as coding, advertising and enterprise tools. Another difference, she said, is supply. Demand for computing power is already outpacing available capacity, while the dotcom boom left huge amounts of unused fibre optic infrastructure.

Even so, she and other market watchers have urged caution on the assumptions underpinning returns, including how long expensive assets remain useful. Michael Burry, the investor famous for warning of the 2007 subprime mortgage collapse, has also sounded alarms about AI exuberance.