Table of Contents

From Buddhist steppes to African villages, the former FIDE president speaks on destiny, noospheric thinking, and why saving Earth means saving the universe.

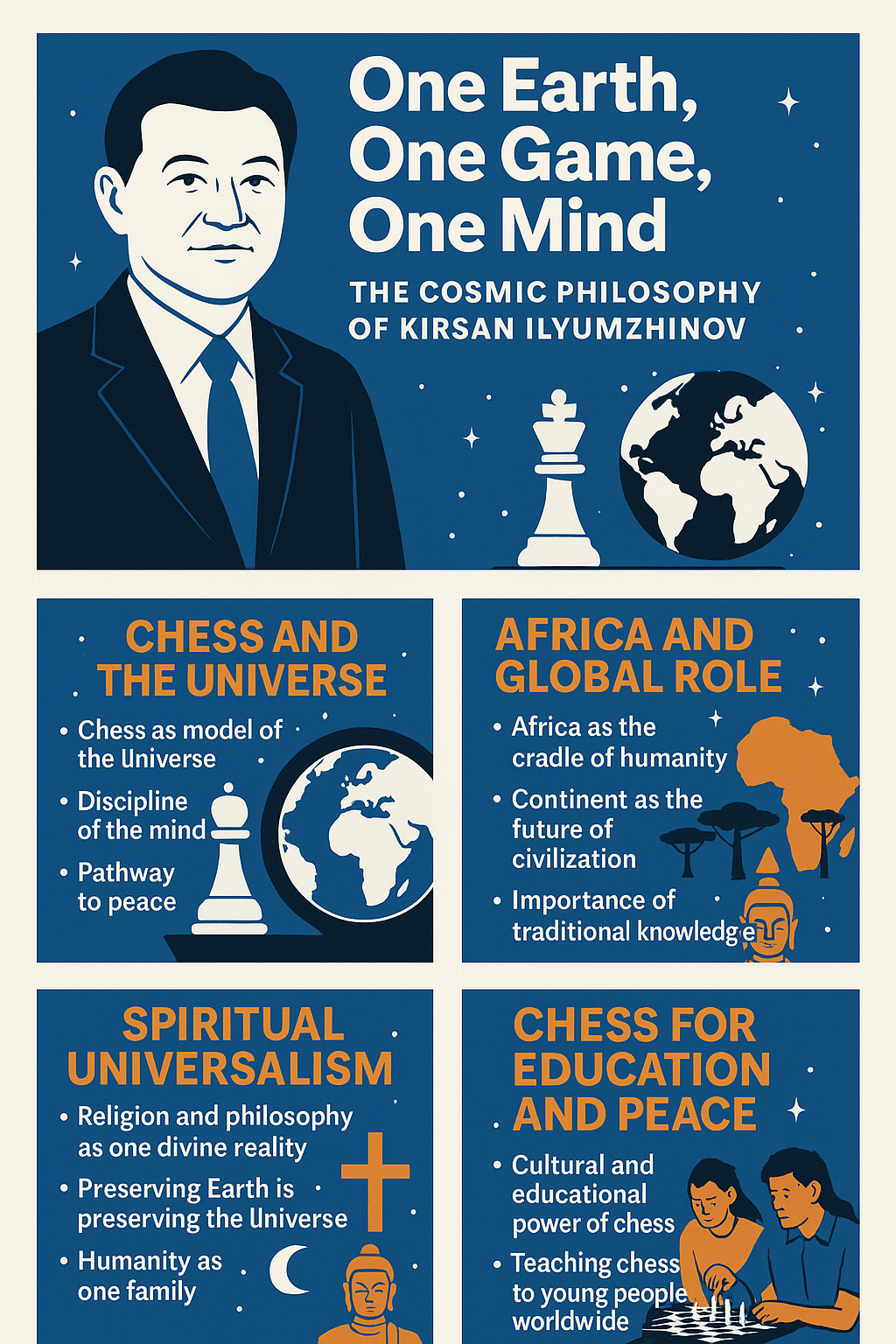

In an era of fragmented leadership and crisis-driven politics, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov stands apart — not only as a former president of FIDE and Kalmykia, but as a thinker rooted in a tradition that spans both the spiritual and the scientific. His worldview evokes the cosmic imagination of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the noospheric ecology of Vladimir Vernadsky, and the moral clarity of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. For Ilyumzhinov, chess is not just a game but a gateway — to peace, to consciousness, to universal responsibility. In this rare and far-ranging conversation, he shares a vision in which education, spirituality, and planetary ethics converge — and where saving Earth may well be the first move in saving the cosmos.

But to reduce his legacy to chess titles or political appointments would be to miss the essence of his worldview. For Ilyumzhinov, chess is not simply a game; it is a model of the universe, a discipline of the mind, and a pathway to peace. Spiritual traditions are not competing truths, but reflections of a single divine reality. And the future of humanity, he believes, will depend not on power or profit, but on our capacity for ethical action, planetary consciousness, and inner transformation.

He speaks of Earth not as an isolated planet, but as an integral part of a living cosmos — and warns that the fate of one cannot be separated from the fate of the other. Preserving the Earth, he insists, is preserving the universe itself.

In this rare and expansive interview, Ilyumzhinov reflects on the spiritual grounding of his childhood, the moral clarity forged in historical trauma, and the sacred duty he sees in preserving peace — on Earth and beyond. With characteristic candor and philosophical depth, he speaks on Africa’s global role, the educational power of chess, the responsibilities of leadership, and the importance of noospheric thinking in an age of division.

He also addresses his ambitions to return as FIDE president — and with that, to lift politically motivated sanctions imposed against him, which he views not only as unjust, but as an obstacle to his life’s work of promoting peace, unity, and cultural understanding through chess.

This is not a typical political conversation. It is an invitation to think bigger — about who we are, what we are meant to become, and how a seemingly simple board game might just help us get there.

— Where did you first find spiritual grounding — in religion, philosophy, or nature?

— Religion helps a person peer into the depths of their inner world; philosophy reveals the structure of the universe around us. Nature, meanwhile, is the embodiment of the divine design — and the ultimate justification of all philosophy, which without nature loses its meaning.

Where, then, can a person find spiritual footing in today’s restless world, where everything, as we see, is fragile and impermanent?

My answer is this: above all, within oneself. But the soul must contain religion — as a foundation; philosophical principles — as the capacity to pose difficult questions to oneself; and a love for nature — for a human being is part of it.

I came to understand this quite early in life — and perhaps, it is only thanks to this understanding that everything else became possible.

— Which teachers or texts awakened in you a sense of planetary or cosmic identity?

— A wise person learns throughout their entire life. A foolish one learns nothing, convinced they already know everything.

I often return to the works of the great Confucius. I have also read the Pali Canon — a collection of sacred Buddhist texts. The Christian Bible and the Muslim Quran are always within reach on my desk.

And over the course of a long life, I have read many books in which the greatest minds of humanity shared their thoughts about the world and humanity’s place within it.

Which texts awakened in me a sense of universal identity? The answer is simple — all of them.

You, I, all of us who call ourselves human beings — we are inseparable from the universe. This was the Creator’s will. He gave human beings reason so that they might come to understand this truth.

And from that, profound conclusions follow.

A cosmic identity also implies a corresponding level of responsibility — for the entire universe, of which our planet Earth is an inseparable part.

Someone might say: who needs this unfortunate little planet, lost on the edge of the Milky Way, on the outskirts of the universe? But they would be wrong.

By preserving the Earth, we preserve the entire cosmos. And the reverse is also true: if we allow ourselves to destroy Earth in the flames of nuclear war, we destroy the entire creation.

— When you were a young politician, were you more interested in power — or in transforming society?

— When I was young, I’ll be honest — what interested me most were young, beautiful women.

As for your question — it is not quite accurately phrased.

How can one think about transforming society without possessing power?

The real question is: what do we mean by power — and what kind of transformation are we speaking of?

The second depends entirely on the first.

Tyrannical power seeks one thing only — the merciless suppression of dissent. Under tyranny, all "reforms" merely refine the instruments of oppression against an already disenfranchised population.

Enlightened power, by contrast, is directed toward defending the rights of citizens and ensuring their dignity. We have known such examples — in both past and present.

Power attained through direct and honest elections — if, and only if, the results truly reflect the will of the people (which is not always the case) — grants broad authority, but little time to exercise it. And so, immediately after an election, the “chosen ones” begin preparing for the next — and for everything else, there is no time left.

In my youth, I cannot say I thought deeply about these matters.

I entered politics at what was likely the most dramatic moment in my country’s history — a change of epochs, the collapse of a great nation, and deep concern that even the remnants left to Russia after the fall of the USSR might be lost.

Thanks to God, the politicians of that time had the wisdom and resolve to resist regional separatism and erect a firm barrier against destructive centrifugal forces.

I am grateful that I was able to contribute to the collective effort to preserve Russia.

— You have called Africa “the cradle of humanity” and “the future of civilization.” What drew you to the continent not only politically, but spiritually?

— I tend to agree with those scholars who believe that humanity had several independent cradles.

But that Africa is among the most significant of them — if not the central one — a foundational point helping shape the future course of human development, that is beyond doubt.

From my very first encounter with the African continent and its people, I was struck — even overwhelmed — by its nature: the riot of color, the richness of plant and animal life, all of which is simply taken as the norm.

Equally profound was the impression made by the sincerity and openness of Africans.

This is not what one might call simplicity or naïveté.

It comes from nature itself — from its strength. For the strong are always sincere, and trusting.

— You worked closely with African leaders such as Nelson Mandela, Jacob Zuma, and others. What spiritual or moral qualities did they share?

— Above all, I would say: purposefulness.

And that, in turn, rested on an unbreakable will, loyalty to principles, and a selfless devotion to serving their people.

These are truly great individuals of Africa, whose names are forever inscribed in the Golden Book of Humanity’s Glory.

— In your view, what role can traditional African knowledge play in the development of global consciousness?

— The wisdom of any people is priceless.

The traditional knowledge of Africa’s peoples is unique — there is no substitute for it.

That is why I am confident: this knowledge will play a vital role in shaping a multipolar world.

Africa itself is a living model of multipolarity.

— You brought chess to villages, schools, and remote communities across Africa. What did these encounters teach you about the spirit of African youth?

— African youth are second to none in what we call strength of spirit and hunger for knowledge.

I was fortunate to see this with my own eyes every time I traveled to remote places — deep into the African heartland, where young people had never heard of chess.

And how eagerly, how voraciously they took to learning this new game!

It was simply marvelous.

I am confident that we will soon hear of an African chess player contending for the world chess crown.

And I, for my part, will do everything in my power to help make that a reality.

— Do you believe the African Union should play a more active role in global cultural and educational diplomacy?

— Without question.

For a long time, human civilization has been oriented along the East–West axis.

Today, that vector is shifting.

In the 21st century, it will be the North–South axis that determines the direction of global development.

And in this, the African Union has a crucial role to play in shaping the priorities of our shared future.

— What new initiatives between Africa and the rest of the world would you support — in the spiritual, scientific, or educational spheres?

— Without a moment’s hesitation — I support all initiatives, in every sphere, that are aimed at strengthening Africa’s spiritual, scientific, and educational connections with the rest of the world.

I have always supported, and will continue to support, every African initiative aimed at strengthening the role of African states — and of the continent as a whole — in determining the course of a multipolar world.

— You grew up in Kalmykia — a unique Buddhist republic in Europe. What early experiences shaped your view of humanity as one family?

You’ve put it well: my small homeland, Kalmykia, is unique in every respect. It’s hard to convey in words — you need to see it for yourself: the breathtaking beauty of the steppe in spring, in bloom, stretching to the horizon where the edge of the earth meets the sky. That feeling — of being close to the sky, to God — as I later came to understand, was one of the most powerful impressions of my early childhood.

So many years have passed, and yet I clearly remember — I must have been five or six — how my beloved grandmother, when my parents went off to work, would lock the doors, draw the curtains, and pull a small statue of the Buddha from an old, large chest. She would lay out a rug on the floor, hang a Buddhist thangka, and light a small lamp. She prayed to the Buddha — for mercy upon her children and grandchildren, upon all our relatives, and all of Kalmykia.

She used to say, “And for all our native land.” Write that last word with a capital letter, and you’ll get “Earth” — the whole planet. That, you see, is planetary thinking. Because one cannot imagine true well-being in any one corner of the earth if everywhere else there is war, suffering, and destruction.

Grandmother made me pray as well. Not by force — no. But by the power of her example.

One day, I asked her why we could not pray openly, why we didn’t go to temple. She replied: “We have no temple. But every believer has one in their heart.” And then she said, “You’ll grow up one day — and you’ll build a temple, and people will come there.”

I did grow up — and once I had the means, I set out to fulfill my grandmother’s wish. I built 46 Buddhist temples, prayer houses, and stupas in Kalmykia — among them, the largest Buddhist khurul in all of Europe. I also built 22 Orthodox Christian churches in the republic. In Elista, the capital, I built the largest and most beautiful Kazan Cathedral. In 1997, the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, Alexy II, came to consecrate it.

The Patriarch also visited a church in the village of Priyutnoye, not far from Elista — the Church of the Exaltation of the Cross. It was the very first one I built in Kalmykia.

And here is what matters most:

I myself am Buddhist. Yet I was sincerely glad to have the chance to help Christians draw closer to God in their own churches. And I remember how happy the Buddhists were when a beautiful Orthodox church appeared in their village. Just as the Orthodox in Kalmykia rejoiced when the largest Buddhist temple in Europe was built in Elista — a magnificent khurul, constructed according to every sacred canon, down to the smallest detail.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama himself came from Tibet to bless the site where that Buddhist sanctuary now stands.

God may be called by different names — but He is One.

He dwells in the heart of every believer, and in every place where the faithful gather to pray.

God is one. And humanity is one family.

— Was there a moment in your childhood or youth when you first felt your life might have a global — or even cosmic — purpose?

I’d rather not give readers the impression I suffer from delusions of grandeur. I do not, believe me — though, I must admit, I have accomplished enough in life that, from time to time, it would not be a sin to wonder whether one has a destiny, or a mission to fulfill.

Every person has a calling — a purpose.

Sadly, not everyone manages to understand it in the course of their life — or to accept what they were meant to become or achieve.

Let us remember: Christ and the Buddha were born as ordinary human beings to ordinary women. The Prophet Muhammad, who delivered Allah’s word to the suffering, was also — like all of us — simply a man. Yet billions of people across time have been — and will continue to be — grateful to them for fulfilling their destinies.

Anton Chekhov once said:

“The calling of every person lies in spiritual work — in the constant search for truth and the meaning of life. Only then will everything in a person be beautiful — their face, their clothing, their soul, and their thoughts.”

Forced labor and a life without hope do nothing to enhance beauty.

That vision — of a life devoted to inner meaning — is very close to me.

In Buddhism, the search for meaning is central to spiritual practice. Its ultimate goal is enlightenment, or liberation through a transition into a higher state of being.

Those who revere the Buddha as divine call this reincarnation — a return, a rebirth. But it is necessary only for one purpose: to fulfill one’s purpose and continue the search for ultimate meaning.

— Your family and people endured deep historical trauma. How has that ancestral memory shaped your compassion and drive to act?

It wasn’t only the Kalmyks who suffered under Stalin’s repression — the darkest chapter in our history. Many small peoples across the Soviet Union endured what it means to be torn from one’s homeland and exiled to harsh, uninhabitable lands.

Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Meskhetian Turks — and of course, Kalmyks — all carry the scars of that era. The operation against my people was called “Ulus” — a cold, bureaucratic name for what was in truth a deep wound, a knife across the fate of a nation.

Naturally, my own family shared in those sufferings.

In Elista, there is a monument by the artist Ernst Neizvestny. It is dedicated not only to the deportation of the Kalmyk people to Siberia — but to what they brought back with them, 14 years later, when they returned from exile.

Our national poet, David Kugultinov, wrote it best:

I knew that in the forests of Siberia,

My people found friends — and their souls grew strong again,

Among the best of Russians,

Among the most generous on Earth,

Who shared with us both fate — and bread.

And so, there you have it: with love for the Russian people, the deported Kalmyks returned from Siberia — returned with hope and faith in a better tomorrow.

That is the greatest inheritance we descendants received from our resilient, unbroken ancestors: Love for the Motherland. Faith in God. And belief in our own strength.

These are the principles that have always guided my actions — for Kalmykia, and for its people.

— You’ve said that chess is not just a game, but a spiritual and educational tool. What makes chess so universal?

I must confess — there’s one version of chess’s origin I’m especially fond of. It’s more legend than historical hypothesis, but it’s beautiful — and reveals the deeper essence of the game.

There’s a theory that chess was brought to India by the Aryans, who had migrated from Hyperborea after that land was struck by cataclysmic global forces.

Many perished — nearly half — but the survivors fled toward the Ural Mountains. Some later settled in Siberia, while others crossed the Hindu Kush into India — near the intersection of the Pamirs, the Karakoram, and the Himalayas.

The Aryans brought with them Sanskrit, in which the Vedas — the Book of Knowledge — were written. Alongside this, they brought three great games: cards, billiards, and chess.

(There’s much to be said about cards and billiards — and I’d love to discuss them another time. It’s a fascinating subject.)

But about chess, I will say this: chess could not have been invented — it was revealed.

It is a model of the world. A model of life, with all its twists and turns. That is what chess is.

It is not just a game.

Dumbbells and barbells strengthen muscles. Archery and marksmanship train calm, focus, and precision. Different sports train different parts of the body.

But only chess strengthens the mind.

And if we are speaking of intellectual development, there is no greater tool than chess. That is why it must be an essential part of education. This is the reason why, during my time as FIDE president, I championed the global project “Chess in Schools.”

And I intend to do even more.

— What’s the most transformative moment you’ve ever witnessed when teaching someone to play chess?

I remember it from my own childhood — from when I was first learning the game.

Any rowdy child — once they sat down at the board — would become quiet, calm, peaceful.

Peace of mind — that is chess’s most amazing, almost miraculous gift.

This is precisely why I believe we must support the project known as the International Association of Chess Amateurs (IACA) — a comprehensive initiative to introduce people to the game, nurture their love for it, and thus — foster peace in every corner of our planet.

And for that, no effort is too great.

— Can chess help young people develop a global or noospheric intelligence — the ability to see the whole field?

Noospheric thinking is essential for the existence of a global intellectual-information system — one capable of guiding the self-organization of society.

Today, we witness the crisis of the old model — one in which man is certainly not his brother’s keeper, and ancient codes call for “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

But a multipolar world demands something different: cooperation, interaction, harmony amid difference — even with varied traditions and cultures.

And if that is indeed the case, then chess can teach young people to see the entire picture of existence — made up of diverse elements, all operating by shared rules, interwoven in mutual influence.

And so, I say: teach your children to play chess. Develop their noospheric thinking.

For it is they who must live in the new world. They must learn to see more — and think deeper.

— If you were to return as FIDE president, what would be your first act — not just as a sporting gesture, but a spiritual one?

First and foremost — a total and uncompromising rejection of any form of discrimination against chess players: political, national, racial, or otherwise.

Chess is a great game for one more reason — because across the board, king and peasant are equal. There is no distinction until the first move is made. And only then will the board reveal who rules — and who falls into servitude, subject to nothing but the strength of their opponent’s mind.

— Would you support the creation of a continental African Chess Academy with a focus on ethics, philosophy, and education?

— The International Chess Federation (FIDE) unites national federations as its members. These are grouped into 27 zones based on geography. Each zone elects its own zonal president, who represents its interests within FIDE.

Africa comprises five FIDE zones under Zone 4, encompassing 50 national chess federations. For example, countries like Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia belong to Zone 4.1 (North Africa); Ghana, Nigeria, and Côte d’Ivoire fall under Zone 4.2 (West Africa); while nations such as South Africa, Zambia, and Namibia are part of Zone 4.5 (Southern Africa). These zones coordinate regional tournaments, development programs, and representation within FIDE’s global structure.

Without question, for all of us who see chess as more than a pastime or entertainment, it is time to think seriously about uniting chess players and enthusiasts in deeper ways.

Whilst we already have an African continental chess association known as the African Chess Confederation, the idea of establishing a unified Chess Academy in Africa — one with a strong emphasis on ethics, philosophy, and education — would be of immense value.

Such an Academy could help develop chess in African countries where domestic resources are limited — or, at times, simply not there at all. But this is precisely where the true power of chess lies: the more people in a country who know how to play chess, the better that country tends to perform — in its economy, in its culture, and across all areas of life.

So I say this with confidence: if I return as FIDE president, I will wholeheartedly support the creation of an African Chess Academy.

— Should chess be recognized as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage under the auspices of the UN or UNESCO?

— But is it not already so, in essence?

What could be more deserving of global cultural recognition than chess? The real question is: what meaning do we now choose to give to the term “cultural heritage”? How will we implement that meaning — and with what resources?

UNESCO, we must admit, is going through challenging times. The United States has announced its withdrawal. Countries such as Canada, Poland, Japan, and Israel — among others — have stopped paying membership dues.

So, while it is possible to imagine many fascinating and worthwhile initiatives to promote chess under the UNESCO banner, we must first ask: what would this actually mean, and how would it work in today’s complex and fragile global environment?

— If you were to return as FIDE president, what would be your three top priorities in the first year?

— I have already touched on one: above all, I would work to eliminate every form of discrimination within FIDE — whether on the basis of race, nationality, ethnicity, politics, or geography.

Chess must be above politics — and outside any ideological or geopolitical struggle.

A second priority would be to support the development of amateur chess through the International Association of Chess Amateurs (IACA). After all, every chess genius, every world champion, began their journey as an amateur. And I’ll say this: I’ve never heard of a single person who achieved anything meaningful in chess without loving the game first.

Finally — and I consider this of utmost importance — we must dedicate ourselves to the consolidation of the global chess community. In chess, rivalry should exist only across the board during play — never behind the scenes, through intrigue or sabotage.

— Under your leadership, chess expanded across the world. Yet many say FIDE has again become overly Eurocentric. How will you ensure fairer representation for Africa, Asia, and Latin America?

— You’re right. As FIDE president, I visited more than 180 countries across every continent. I met with numerous heads of state, always seeking their understanding and support.

We must restore to chess what in politics is called multipolarity. That means ensuring the voices of chess players from Africa, Asia, and Latin America are heard just as clearly as those from founding nations of the Federation.

How can we achieve this?

It won’t be easy. But we must begin by holding major tournaments — championships, Olympiads, and team competitions — in all corners of the globe. This will spur local development and elevate the importance of zonal organizations.

— In the past, you brought chess into schools, villages, and family homes. Would you scale this model once again? What would be new in your approach?

— Not only would I — I will. Chess, without question, makes a person more intelligent, more noble, more pure in thought.

What innovations are needed? Above all: internet access — even in the most remote areas.

If there is connectivity, there is communication — and that creates opportunity. The greats of the chess world — its legends — could reach the most distant corners and offer lessons to beginners. Young people follow their heroes; they imitate them. That is why this approach has enormous potential.

Chess is also tremendously popular in prisons across the world. Tournaments are regularly held among inmates. I have supported — and will continue to support — these efforts, because I believe deeply in the redemptive and civilizing power of the game.

— Do you see FIDE not just as a governing body, but as a platform for peace, youth education, and digital inclusion?

— That is the only way it should be seen. Chess, by its very nature, is the game of peace.

The Muses fall silent when cannons roar — and Caïssa, the Muse of Chess, is no exception.

Let me remind you: the god of war, Mars, fell in love with Caïssa’s beauty. And it was only through chess that he won her heart — and gave up war.

Chess, then, is a game for people who love peace.

As for youth education — the results speak for themselves. In Kalmykia, we introduced chess as a compulsory subject in schools. Immediately, overall academic performance improved.

Digital inclusion is now a fundamental requirement for the development of society. You cannot play football or hockey by correspondence — but chess, you absolutely can.

In that sense, chess is a perfect entry point for young people into the digital world.

— Chess is evolving rapidly with the rise of AI, online play, and new formats like blitz and Chess960. What role should FIDE play in shaping the future of the game?

— The most active role possible.

That is why FIDE exists — to help shape the future of chess.

It’s not about changing rules that have lasted for centuries — or inventing new pieces (though enthusiasts certainly have no shortage of imagination). The future of chess lies not in exotic variants, but in this: how many people will love and play the game tomorrow?

Without players, there is no chess.

Our goal is clear: to ensure that at least one billion people on this planet play chess.

Today, we estimate that over 600 million people play — which means there is still a long way to go.

And we will walk that path.

— How do you plan to work with chess federations and sponsors so that your return is seen not as a disruption, but as a continuation of global progress?

— That is precisely the challenge — to ensure continuity and forward movement, so that FIDE is perceived not as restarting, but as evolving in a positive, progressive arc. That’s always been the case: each historical period has brought its own tasks, its own challenges for FIDE to solve.

When the global chess community entrusted me with leading the organization, the situation was far from easy. The budget was so limited, we could barely cover essentials — let alone offer fair prizes for world championship winners.

So, how did we begin? Why did sponsors believe in us?

With something simple: openness and truth.

We spoke clearly about our goals and offered a transparent, realistic path toward achieving them. Influential figures from the most developed countries believed us — and entrusted us with significant resources to build the future of world chess.

These records are open: anyone can see that during my tenure, FIDE’s budget multiplied several times over. Progress was made in every direction.

And why did it work? Because we built honest, transparent, and respectful relationships — with both sponsors and national federations. I believe many in FIDE’s current leadership, many of whom joined through my support and mentorship, will remember that — and respond with a willingness to cooperate for the greater good of global chess.

— Would you support the creation of a permanent FIDE regional headquarters in Africa to deepen development across the continent?

— Not only in Africa! The need to establish FIDE regional headquarters on every continent is long overdue. The closer an organization’s leadership is to the lived realities of society — to day-to-day challenges and local concerns — the more effective its work will be.

— You’ve said that leadership must be rooted in spiritual clarity. What practices help you maintain balance amid global uncertainty?

— I am a Buddhist. Every morning begins with the sacred mantra: Om Mani Padme Hum. There’s no need to make a spectacle of it — no need for others to even notice. You pray for yourself, and only for yourself. You can recite the words aloud or whisper them within: “Hail to the jewel in the lotus.”

These words have helped countless people around the world find peace — and the strength to believe in themselves.

The Buddha taught that, despite all his wisdom and divine qualities, he could not remove human suffering for us. His message was simple: each person must take responsibility for their own life.

If we wish to eliminate suffering, we must first eliminate the causes that lead to it. If we want to be happy, we must cultivate the causes of happiness.

Buddhists believe that this is within reach — through ethical living, through respect for moral law. And whether or not our lives become what we hope for depends solely on our willingness to change ourselves.

— You’ve spoken of the noosphere — a planetary field of thought. Do you believe we’re entering the next phase of human evolution?

— We already have — only, not everyone realizes it. And of those who do, not all are ready to accept it.

What is the essence of noospheric thinking? It’s this: humanity must recognize itself not as master of nature, but as part of it. We are not kings entitled to dominate or destroy at whim.

In the Soviet era, one slogan became popular: “We can’t wait for nature’s favors — we must take them ourselves.” And take we did — so aggressively that species vanished, fertile lands became desert, rivers and even entire seas disappeared.

Humans became enemies of nature — and nature began to respond in kind: with drought, famine, disease.

The French philosopher Édouard Le Roy first proposed the idea of the noosphere. It was the great Russian thinker Vladimir Vernadsky — philosopher, biologist, ecologist, chemist, geologist — who developed it into a fully formed system.

To keep it simple: we have no choice. Either we accept that we belong to a living planetary system, with all the responsibility that implies — or we perish. There is no third path.

— Thinkers like Tsiolkovsky and Vernadsky spoke of humanity’s cosmic destiny. How did their ideas shape your worldview?

— Directly and profoundly. What other effect could true wisdom have on a person who takes thinking seriously?

The great minds of humankind have already spoken most of what needs to be said about how to live a meaningful, joyful life — among our loved ones, in harmony with the Earth.

All that remains is to truly listen to their words — and act on them.

— Could it be that traditional African wisdom — based on connection and harmony — is already noospheric in nature?

— Without a doubt. And not just African traditions — every culture holds a treasury of wisdom refined over thousands of years. But Africa, as one of the cradles of civilization, proves best that only through deep connection with nature can humanity reach the heights of its potential.

— Tsiolkovsky said: “Earth is the cradle of humanity — but one cannot live in the cradle forever.” Is humanity ready to grow up?

— I’m afraid the honest answer may disappoint: not really. In fact, we must acknowledge the opposite — humanity has not yet matured. And worse, it often resists doing so.

— If you could gather Buddhist monks, African sages, and Western scientists — what would you ask them to work on first?

— On the most important question of all: why can’t we live in peace?

Why do we still kill one another?

Do you know how many days of peace exist in recorded human history?

Not one.

Every day, somewhere, someone is at war. Sometimes in just one region — and sometimes everywhere at once. Then we call it a world war.

— Are the world’s crises a sign of shifting consciousness — or a warning from Earth itself?

— I tend to believe the Earth is alive — and wise.

She welcomed us, gave us all she had. And now, she is sending us signals: wake up. Come to your senses. Be wise.

Are we listening?

Sadly, not yet.

— You’ve walked between East and West, between science and spirituality, politics and poetry. How do you maintain inner harmony?

— You may not believe me, but it’s quite simple: don’t just say your prayers — believe in them.

In today’s tense, polarized world, maintaining inner balance is extremely difficult. But I’ll say it again: only we are responsible for our own peace of mind. And that peace is the foundation of peace on Earth.

— What is your greatest hope for the youth of Africa?

— Energy. Perseverance. Creative force — that is what I see in Africa’s young generation.

Let’s be honest: in much of Europe, we see signs of apathy, of fatigue, of disconnection among youth.

Africa — once the cradle of civilization — now stands as the place where the future of humanity may rise again.

That is my deepest hope.

— How would you like to be remembered: as a politician, a philosopher, or a servant of the planet?

— But weren’t Aristotle and Plato servants of the planet?

In my view, that’s what philosophers are meant to be — those who help life on Earth take on meaningful form.

— If you could write a message for future generations to read a thousand years from now, what would you say?

— Just this:

We tried to do our best so that you could live.

Now, do your best — for those who will come after you.

A King’s Gambit for the Planet

In a world often driven by power, profit, and polarization, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov presents an altogether different paradigm — one in which the movements of a chessboard reflect the movements of civilizations, and where the moral weight of leadership lies not in conquest but in care.

His journey — from the steppes of Kalmykia to the halls of the African Union, from Buddhist mantras to diplomatic missions — is not the path of a conventional politician, but that of a planetary thinker. To speak with Ilyumzhinov is to be reminded that our most urgent crises are not technological, but spiritual; not logistical, but ethical. For him, the true game is not chess — but the deeper struggle to awaken the mind, open the heart, and align the soul with the cosmos.

At the center of his philosophy is a radical proposition: that Earth is not an isolated rock floating through space, but a sacred node in a living universe — and that preserving it is an act of cosmic responsibility. In that view, Africa is not simply a site of geopolitical interest, but a spiritual anchor for humanity’s next chapter — a wellspring of wisdom, resilience, and generational hope.

Ilyumzhinov envisions a world where temples and technology, ancient wisdom and AI, monasteries and microchips can coexist. In that vision, chess is not merely a game but a blueprint — a shared language of strategy, ethics, and imagination that can bridge nations, races, religions, and generations.

And in that spirit, his message to youth — and to those who lead them — is clear: develop noospheric intelligence. See the whole. Think beyond borders. Act with courage. And above all, preserve peace — for without it, no victory is worth the cost.

In the end, whether or not Ilyumzhinov returns to FIDE, his greatest legacy may lie not in titles or tournaments, but in a larger question he dares us all to ask:

What if the fate of the cosmos really does depend on how we play this game — here, now, on Earth?