Table of Contents

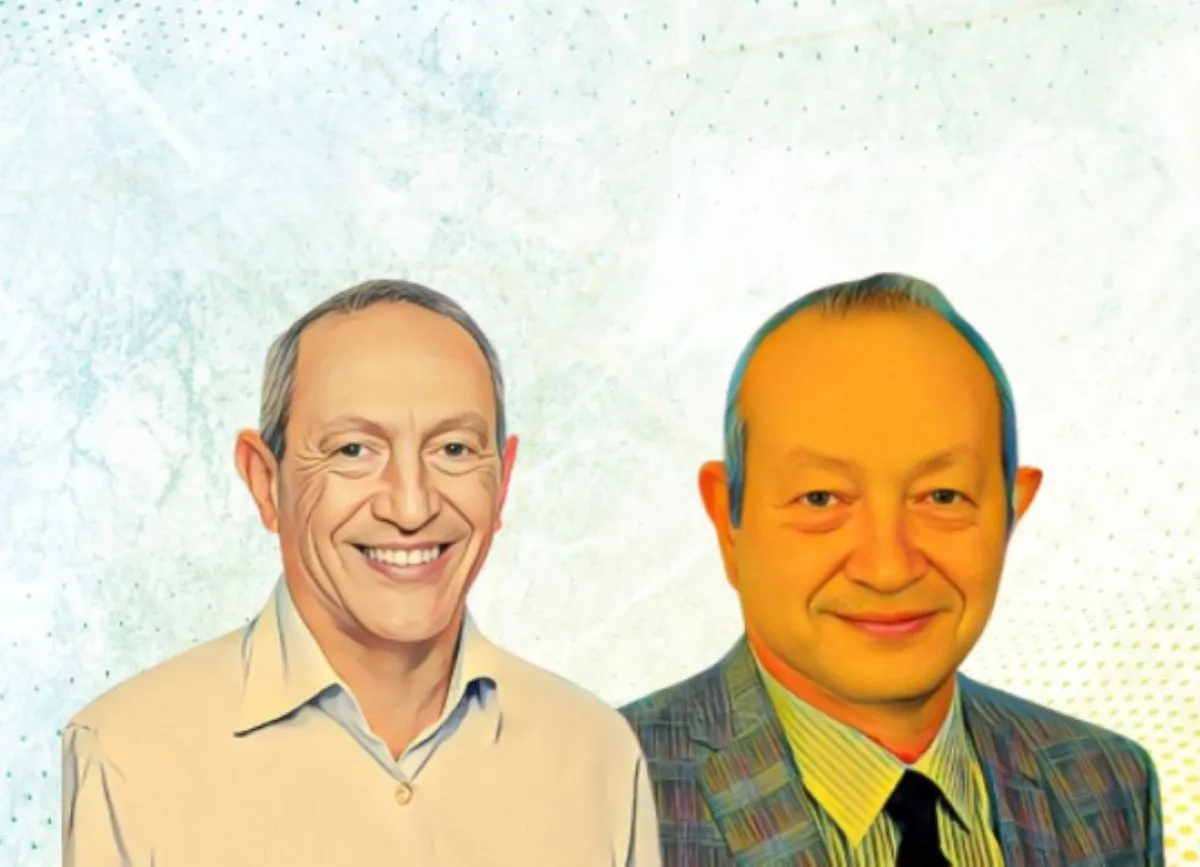

A commercial court outside Paris has placed Brandt, the French home-appliance maker owned by Algeria’s Cevital, under judicial receivership, a move that freezes debts and keeps operations running while administrators look for a rescue plan. The decision hands Issad Rebrab — Cevital’s founder and long regarded as Algeria’s richest man — one of his toughest tests in Europe since buying the storied brand a decade ago.

The Nanterre court opened the procedure on Oct. 1 for both Groupe Brandt and Brandt France after months of financial strain. The court-supervised process allows time to find an investor or craft a restructuring plan, while shielding the company from creditor actions.

What the court ordered

Judicial receivership in France is meant to stabilize a distressed company while a plan is negotiated. In Brandt’s case, management remains in place under the oversight of court-appointed administrators. The company employs about 750 people in France, producing appliances under the Brandt, De Dietrich, Sauter and Vedette labels. Its production sites are in Orléans and Vendôme, with headquarters in Rueil-Malmaison and an after-sales hub near Paris.

The company said it is reviewing several “serious” approaches from potential partners, with the goal of securing long-term financing and preserving jobs.

Why Brandt matters to Rebrab

Rebrab’s Cevital acquired Brandt in 2014 as part of a push to anchor Algerian industry in Europe and bring manufacturing expertise back home. The Brandt name gave Cevital a flagship in France and a symbol of industrial ambition that went beyond its roots in agribusiness and logistics.

France’s household appliance market has shifted in recent months. A slowdown in housing and shrinking household budgets cut into demand, while higher energy and raw-material costs piled on, leaving the brand still fighting to get back to consistent profits.

For Rebrab, Brandt has been more than a business asset — it has been a statement about Algerian industrial know-how entering the European market. Now the brand’s future hangs in the balance.

Jobs, timelines and what comes next

For now, production continues under court protection while administrators solicit bids or financing proposals. Should a buyer come forward, the court will consider not just the offer’s value but also how many jobs and operations can be preserved. Without an investor, Brandt may have to undergo a more sweeping restructuring, which could include selling off parts of the business.

For Rebrab, the ruling represents more than a financial test. A successful rescue would reaffirm his reputation as the businessman who revived a French industrial name. A drawn-out restructuring or breakup would raise fresh questions about the viability of cross-border manufacturing bets in a period of intense competition and rising costs.

The outcome will reverberate beyond one company — affecting suppliers, regional jobs and the image of an Algerian entrepreneur who invested heavily in building a bridge between the two economies.