Table of Contents

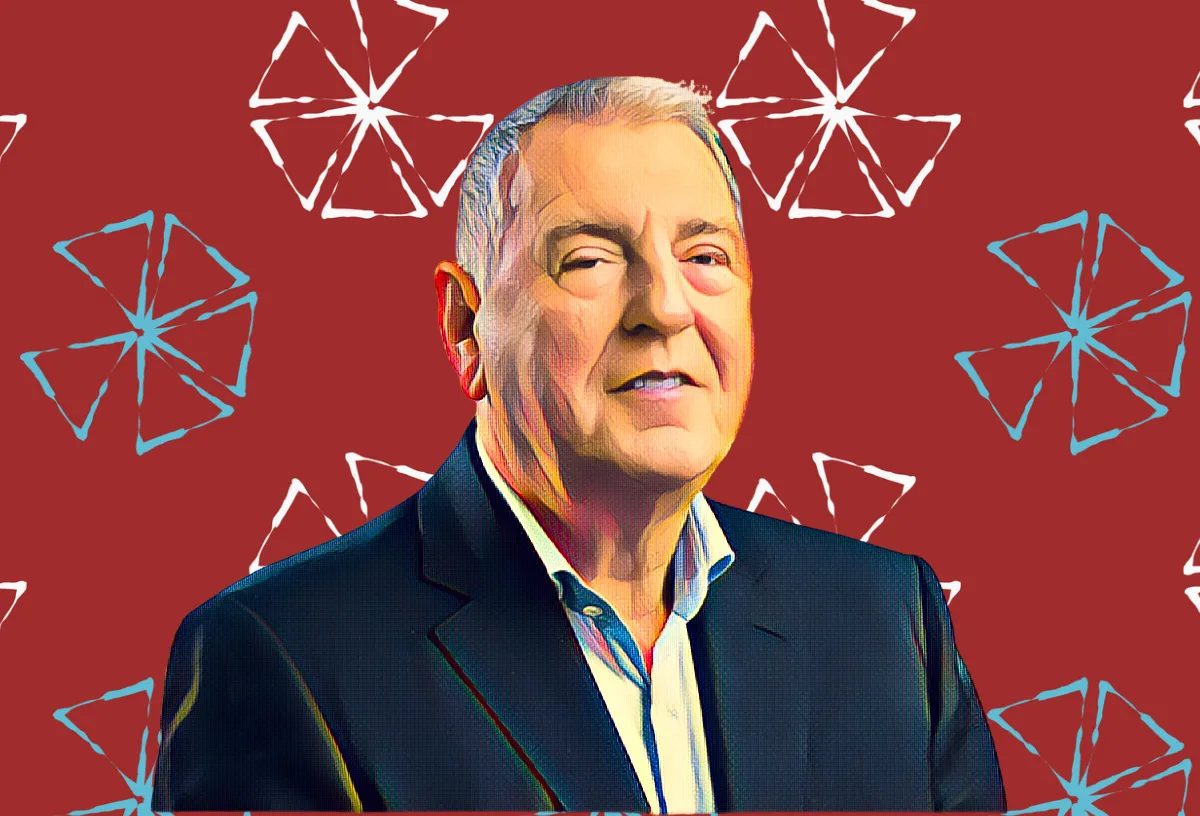

Issad Rebrab, the Algerian industrialist who built Cevital into a global buying force, decided not to pour fresh money into Brandt, and the storied French appliance maker slid into liquidation, ending years of uncertainty for workers and suppliers.

Brandt, a familiar label in French kitchens, had been struggling under a heavy debt load, thinning sales and a market squeezed by low cost imports and tight retail margins. After reviewing the company’s balance sheet and prospects, Rebrab and his team concluded the numbers did not justify a rescue, according to details of the process described in recent reporting and public statements tied to the case.

The decision was not presented as sudden. People involved in the talks said the owner studied Brandt’s assets, its borrowing obligations and whether it could keep operating without burning through more cash. The conclusion was blunt: supporting the company would likely mean financing losses with no clear path to recovery.

Brandt’s problems reflected the reality of appliance manufacturing in Western Europe, where logistics costs are high, competition is relentless and pricing power is limited. Even recognizable brands can struggle when they cannot invest in product renewal, maintain efficient factories and secure volume deals with retailers.

As Brandt’s position weakened, the company was placed under court supervised administration. Negotiations followed. Representatives for the owner held discussions with Brandt management, unions and French judicial authorities about potential routes forward, including partial takeover options that would have preserved selected production lines and some jobs.

Those options did not stick. The financial risks remained too large, and no alternative industrial buyer emerged with a plan strong enough to convince the court that the business could survive.

On Dec. 11, 2025, a commercial court in Nanterre ordered Brandt into liquidation, a move that signaled the end of operations and put hundreds of jobs at risk. The liquidation closed the door on a rescue narrative that had followed the company through multiple owners and repeated turnaround promises.

Rebrab’s reputation has been shaped by bold acquisitions, often of distressed firms, paired with pledges to protect industrial capacity. Brandt shows the limits of that playbook. Sometimes the spreadsheets win, even when the politics and emotion argue otherwise.

The collapse leaves a larger question hanging over France’s industrial landscape: what happens to legacy manufacturers when private capital decides a rescue is too expensive, and public authorities are unwilling or unable to bridge the gap.